Like everyone who enjoys hosting friends and family for meals, I do it for the compliments. “Wow, you have a beautiful home with new stainless steel appliances,” or “Your cooking is wonderful and dredges up memories of infancy,” are some of my favourites. I actually make it a point to always serve some kind of pureed mush because it reminds people of baby food — a recommendation I got from a vintage Martha Stewart tape later decried by Alison Roman in one of her recent YouTube videos.

In the olden days, when a woman wanted to have friends over — for a luncheon, tea, cocktails, a dinner party — she might throw on a hostess gown. A hostess gown was typically a glam affair made of some kind of polyester, was machine washable, and allowed the wearer to transition gracefully between the kitchen to the dining table to the conversation pit embedded in the floor.

In 2011, The New York Times called the hostess gown a “defunct garment,” describing it as “sort of a cross between an evening formal and a bathrobe.” It mostly disappeared after the 1970s, although the idea hasn’t fully vanished. In 2017, Quebec chef and lifestyle writer Marilou launched her “robe a maison,” a comfy, unflattering shmatte that seemed like a joke but was not. NY Mag’s Strategist regularly compiles lists of everyday unitards — there’s a viable market for this stuff.

The idea of loungewear-cum-fancy is inseparable from the years-long conversation we’ve been having about athleisure and the year-long conversation on WFH-wear. I’m still wrapping my head around the fact that people wear their shoes in the house, given my long-standing family tradition of having completely different sets of clothes for indoors and outdoors, disrobing as soon as we’d enter the door. That said, I do wear jeans just to feel something, sometimes.

Fabric used in technical applications, like in exercise clothes, has been finding its way into everyday wear for the better part of the decade. Like jeggings, a terrifying facsimile of jeans, Lululemon’s ABC (anti-ball crushing) pants look like slacks, but they’re made from the same material as their yoga pants. They — and their more affordable Uniqlo knockoff — have been part of my WFH outfit rotation all year, for the days I have enough serotonin to change out of my sleep-onesie. I’ve even worn them to shul with a blazer made of a material I would describe as “forgiving” for a look only somebody my age could pull off without seeming rude.

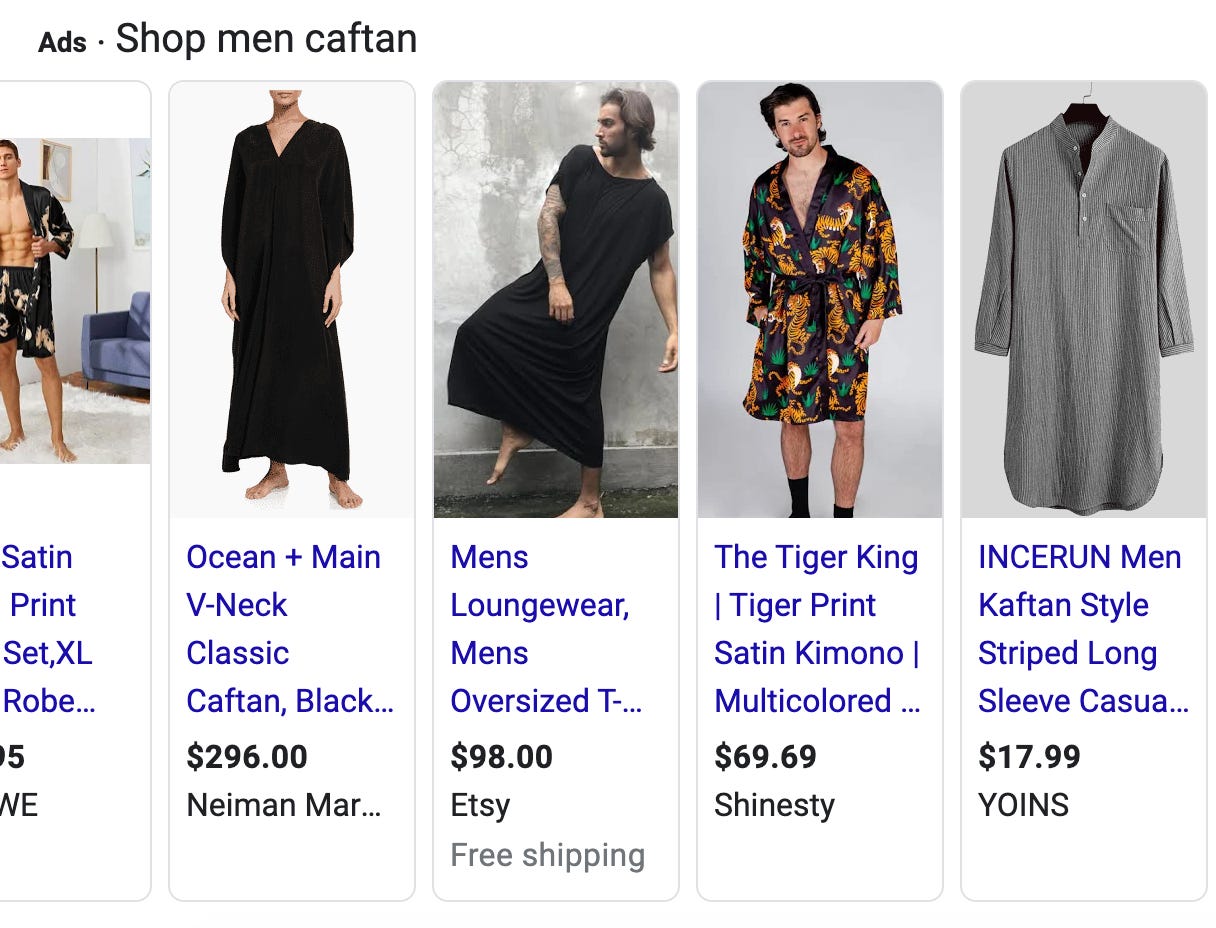

As for hosting? I’ll throw on a sweater. I’m not one to unbutton my pants after a long night of feasting (I’m just… not there yet………….) but I’m sympathetic. I’ve often wished for something even easier — like a jumpsuit in a dark colour that’s perfectly tailored but feels like pyjamas. Or a caftan. Like, come on. I’m tired.

Shabbos shabbos yom menucha…

Our sages tell us that we should beautify ourselves before Hashem in mitzvot. Not only that, but:

“Even if one fulfills the mitzva by performing it simply, it is nonetheless proper to perform the mitzva as beautifully as possible”

This concept is called hiddur mitzvah. It’s the reason why I put stickers on my siddur (kidding not kidding), or why some women wear decked out wigs and tichels, or why men will wear a skillfully embroidered bekishe. Beauty is a Jewish value. Nowhere is this better illustrated than by the phenomenon of the shabbos robe.

Ideally, the clothing we wear on Shabbos should be special. A memorable criticism of Netflix’s Unorthodox was that Esty wore an ugly dress on Shabbos, therefore it was dreadfully inaccurate. Yes, the dress was ugly — but Esty was sad! Personally I found her sheitel to be more distracting.

In real life, dressing for the occasion is no easy task when you’re trying to take care of kids, make Shabbos, and live a complete and fulfilling life all before candle lighting. A shabbos robe gives women the freedom to do all this and more, thanks to forgiving waistlines, durable fabric, and some razzle-dazzle. According to one frum lady on the internet:

“[Shabbos robes are] like a hostess gown. Generally, long black, lycra slinky gowns with beading, rhinestones, bows, ruffles etc.”

Imamother, a message board for frum women, is home to dozens of discussions about shabbos robes. In a 2011 post, “Can someone explain to me Shabbos Robes?” users go back on forth on the pros and cons. They’re comfortable and affordable. My mom wears them all the time. I would never wear them in front of guests, but I’ll wear them around the family. They’re so ugly. I wear mine to shul. They’re great for nursing. Then the conversation was derailed by somebody asking if it’s true that people cover their sofas in plastic ( Yes, it is: “I remember sliding off on summer days.”)

Frum women constitute a unique market when it comes to clothing — especially because tznius isn’t always mainstream. The Jerusalem Post reported in 2007 that US Haredi women were eager to get in on shabbos robe manufacturers’ annual sales in time for the holidays:

A growing concern over the survival of this niche market led a group of retailers and manufacturers this summer to form the Loungewear and Hostess Gown Council, which synchronized sale dates and markup prices.

"We, as a robe business - unlike any other business - have something very unique to give the religious customer," said Beverly Luchfeld, president of Raza Designs, one of the most popular manufacturers of shabbos robes.

"Most of the other merchandise can be found in Walmart, Macy's, etc., but we cater to the needs of this unique customer and should therefore be able to profit."

The robes, an essential part of most haredi women's wardrobes, are typically bought twice a year - before Succot and Pessah. They are designed to be elegant enough to honor Shabbat and holidays, but comfortable enough for women to wear even while working in the kitchen.”

So — the hostess gown never truly died! But the shabbos robe had a bumpy decade. As modest fashion became more popular in the mainstream world, frum women were less frequently relegated to specialty shops in Brooklyn or online stores. Designers like Batsheva, The Frock, and Mimu Maxi became tznius mainstays — thanks to bloggers, Instagram, and mainstream, cross-cultural interest. Adi Heyman, a Jewish orthodox fashion journalist told Aura Schwartz on the Dream Detour podcast:

“[By 2015] it was mainstream to think you could do this and live this life […] and that your fashion was not being compromised because you were just wearing skirts. We had young, modest designers coming up, and their names were out there, people knew who they were.”

In 2020, the Jewish Link wrote that “While Shabbos robe as a concept was losing its luster, maxi dresses have skyrocketed in popularity.” That doesn’t mean they’re going the way of the hostess gown — chas v’shalom — the idea is just being reinterpreted. Vendors like Devorah’s Secret still sell classic black-and-something robes, often with maternity-friendly zippers and buttons. Advertorials for suspiciously affordable robes occasionally pop up in The Yeshiva World.

Maxi skirts, shift dresses, and technical fabric are just changing the landscape. Today, googling “shabbos robe” will take you to retailers like SHEIN and Wish, selling modest and cheap dresses that might disintegrate in the wash, but they’re good enough for a Friday night. Women are no longer relegated to specialty shops in their own neighbourhoods, while taking inspiration from a cottage industry of frum influencers, WhatsApp groups, and fast fashion.

The bare bones of the hostess gown — comfy, glam, durable are scattered across our eclectic, changeable, and slightly lazy taste for clothing. Old customs have a funny way of enduring in the orthodox world, however. Matchmaking, casual hat wearing, the yiddish language. And so too does the hostess gown, made-over a thousand times in the pursuit of hiddur mitzvah and comfort.

PS: Imagine a meeting of the “Loungewear and Hostess Gown Council”. What the heck lol!