It was a late Sunday afternoon and my husband was careening down Benedict Canyon so we made it on time for his cousin’s bris. It was peculiar to me – I’ve never heard of an evening bris, but this was actually all planned. All the women on this side of the family do it, he explained to me. The previous Saturday, the cousin went in for a scheduled c-section so they could make the bris into a huge party. It’s just easier that way.

We turned left onto Cielo Drive and my heart started racing.

“Do you know where we are?” I asked my husband.

“My cousin lives up here,” he said.

“This is where the Manson murders happened,” I said. I looked at Google Maps to see that we had driven past the famous property. I was a little disappointed.

“The what? How do you know that?” he asked. This wasn’t a story covered in yeshiva day school.

The first person close to me who had a baby (not as a teenager) was my friend who owned the cafe where I worked. She was married and they were trying, so it was really exciting for all of us. Her response to becoming pregnant and the uncertainty that comes with it was to learn absolutely everything there is to possibly know about being pregnant, giving birth, and breastfeeding. First, she discovered the app she had been using to track her period had a community function for expecting mothers. They would ask each other a lot of questions like “my doctor says I need to drink water but I don’t like the taste. Can I mix it with Sprite?” or “What is a better name for a boy? Extra or Colt?”

We also discovered that a lot of the women who came to the cafe were doulas or midwives. French Canadian ladies with cropped leggings and henna-dyed hair who suddenly became very interested in her pregnancy. She decided to give birth at the birthing centre with the help of midwives, and after she did she went on to become a doula herself. So for a long time, birth, and the cultures and communities women build around it, was a constant topic of conversation.

Now, nearly a decade later, her kid is like nine feet tall selling Girl Scout cookies and I’m married, living in a religious community surrounded by other young couples and growing young families. If I described my 20s with a metaphor it would be me, kind of stoned, staring at myself in the mirror and picking my nose for a really long time. Enjoyable but not always with the big picture in mind. My 30s, so far, feels like me and everyone I know are all on a merry go round that’s spinning really fast, going from shabbat meals to engagement parties to weddings and simchas to birthday parties and funerals and back around and around and around.

All of that to say is that in the last couple of years, my friends (mostly all married) all did something absolutely hysterical and got into a pregnancy pact. They would never admit it, but there’s no other way to explain the fact that all these women got pregnant all at the same time. I still spend a lot of time talking about birth. You might be surprised right now to hear that one of the hottest trends in the religious expecting mother community is VBACs, or “vaginal birth after c-section,” which I’ve learned never used to be a thing but is now considered extremely covetable – even a point of contention, because some of the women are ferociously competitive.

Just the other day, we sat down with a newly postpartum friend who asked, “do you want to hear my birth story?”

I said yes, of course. My husband was unsure. I asked him if he had ever seen a video or anything of a woman giving birth. He hadn’t because they didn’t really do sex-ed in his yeshiva. Had he seen a diagram? Not really. Had he ever read the Wikipedia article for “cervix” just because he was curious? No.

Since the neighbourhood is built around an active urban oil well, there’s a weird chemical in the air that caused basically all of the women to have boys. So for the last 2 years, nearly every baby born into this community has been a boy, and that means every time I blink I’m at another bris. Always in the same sanctuary, usually with the same mohel, seldom with the same caterer. At the most recent bris, which was on a shabbos, I watched an old lady walk out of the kiddush with a floral centrepiece before the family even made it to the social hall.

Sometimes when we’re driving around, my husband will point to a house and say, “that’s where we had my brother’s bris.” An Ashkenazi bris is always a community obligation, but Persian bris is always a house party. And like I mentioned before, the women usually aren’t terribly concerned about midwives or doulas or about birthing methods like the one where you stand on two bricks inside of a teepee, or push and push and push until it’s time to somersault into a pool. I’ve never heard any of them talk about VBACs.

We pulled up to the house – not the location of the Manson murders – and a valet took our car. The sun was low in the sky and people were congregating around the property. A DJ was setting up on the tennis court, and the eliyahu chair waited empty in the living room. We kissed the cheeks of cousins and family friends, and the caterers twirled around us with pass-around trays. My mother-in-law and I strategically ignored each other by standing in different corners of the house.

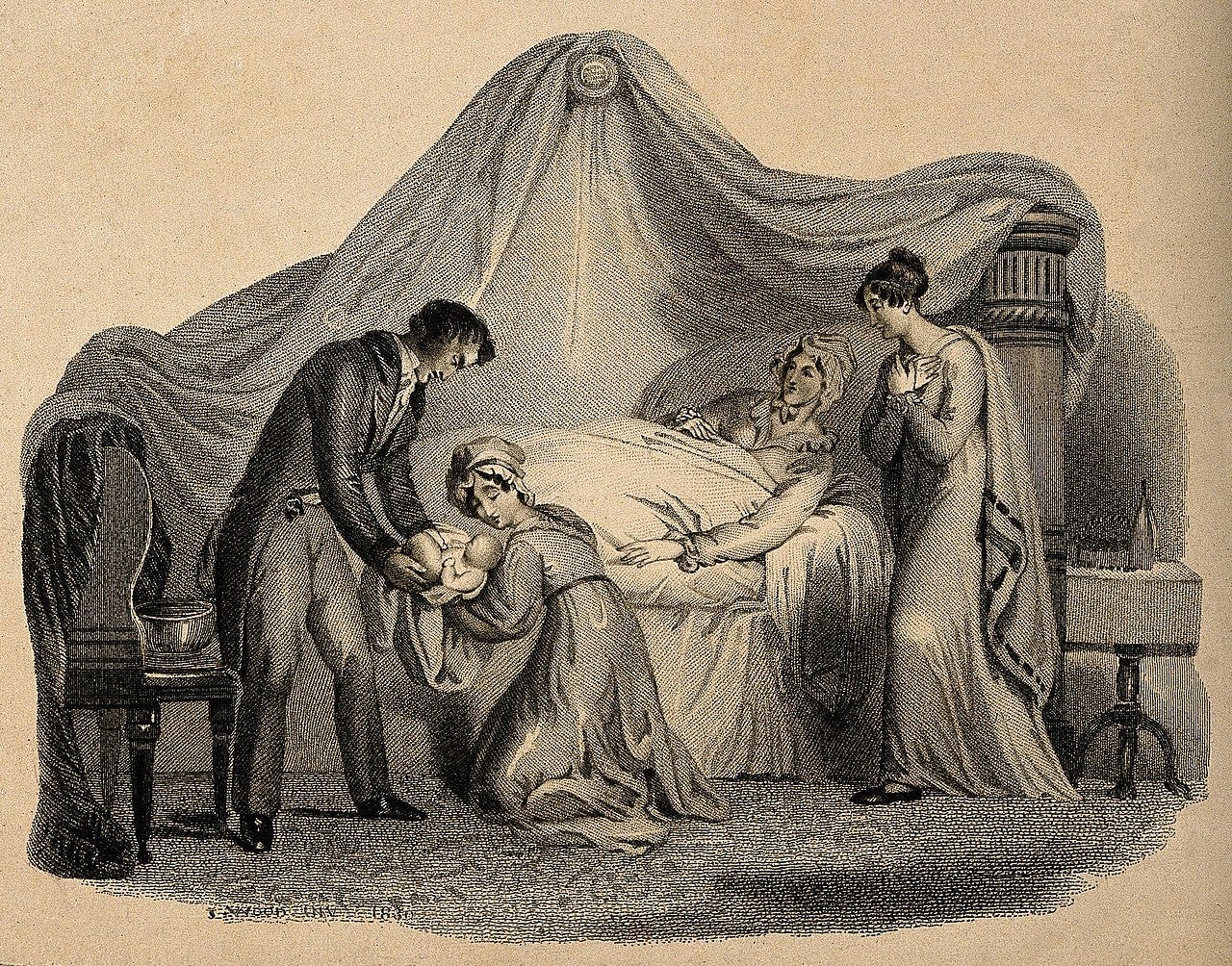

When it was nearly time, the mohel beckoned everyone into the living room. The sandak took his spot in the chair. The mother, wearing an enormous brimmed hat and an off-shoulder white dress, walked into the room with her week-old baby on an ornate satin pillow. The room suddenly felt hotter and more crowded. We looked at each other, smiling uneasily. The mohel said his usual thing about when the baby cries out during a bris, it’s a favourable time to pray, because we have a direct line to Hashem. And who doesn’t want to pray at least a little bit in a moment like this? It’s holy. It’s a rite of passage. It’s obligatory. But it’s a little strange – certainly one that isn’t easily explained to outsiders. But now the father has tears in his eyes, and we can see that the mom is deeply tired.

The baby cries and the gates crack open. He is named for his grandfather, bundled back up, and delivered into the safety of his mother’s arms. The relief is palpable. The rest of their lives have begun. Mom retreats upstairs for the rest of the party, and the crowd moves onto the tennis court to eat and drink and gossip. Some of the people are dancing. We talk about the new name, the upcoming weddings, how the renovations are going. From our vantage point, I see how dark Cielo Drive gets at night, and I imagine the Manson girls running barefoot through the trees, covered in blood. I wonder if it would be less fuss to have a daughter.

I think you’re my favorite writer ever r